Intervals are a vital part of music theory and without them, we would not have music as we know it. In the post, we’ll help you understand what compound intervals are and how to work them our from any note. By the end of it, you’ll be recognising them all over the place!

We are going to dive straight into compound intervals, but if you need a refresher on the basics, check out our complete guide to intervals. This will give you an explanation or major, minor, perfect, augmented and diminished intervals.

What is a Compound Interval?

The basic intervals all fall within an 8 note range, but what happens if our interval is larger than an octave. Simple: they are called compound intervals.

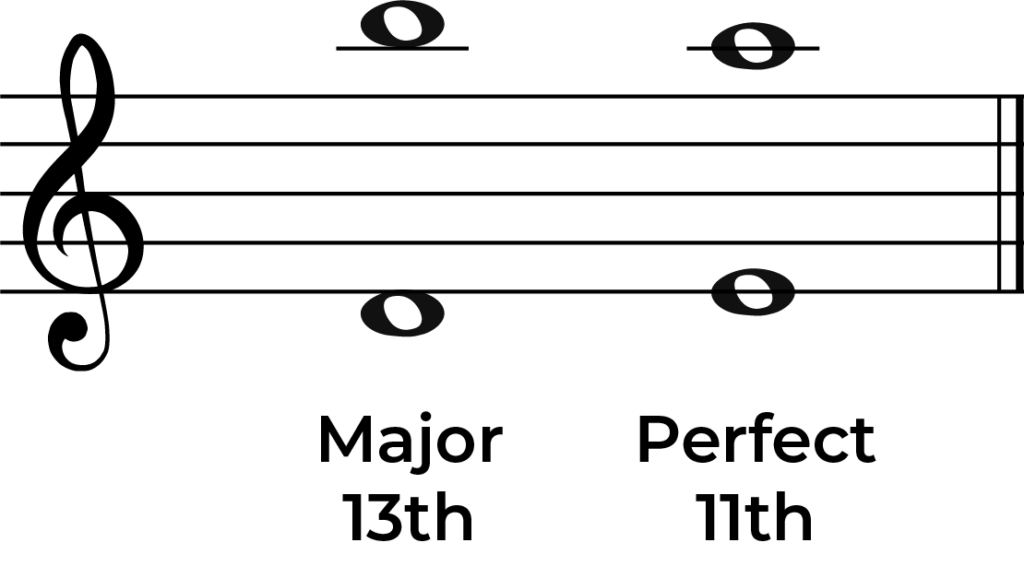

Compound intervals could be named on the degree of the scale. For example, a Major 13th or Perfect 11th. Alternatively, they can be named using the usual notation, but with the word ‘compound’ stuck at the front: compound major 2nd, or compound minor 7th.

With two naming systems it’s important to understand how to calculate compound intervals.

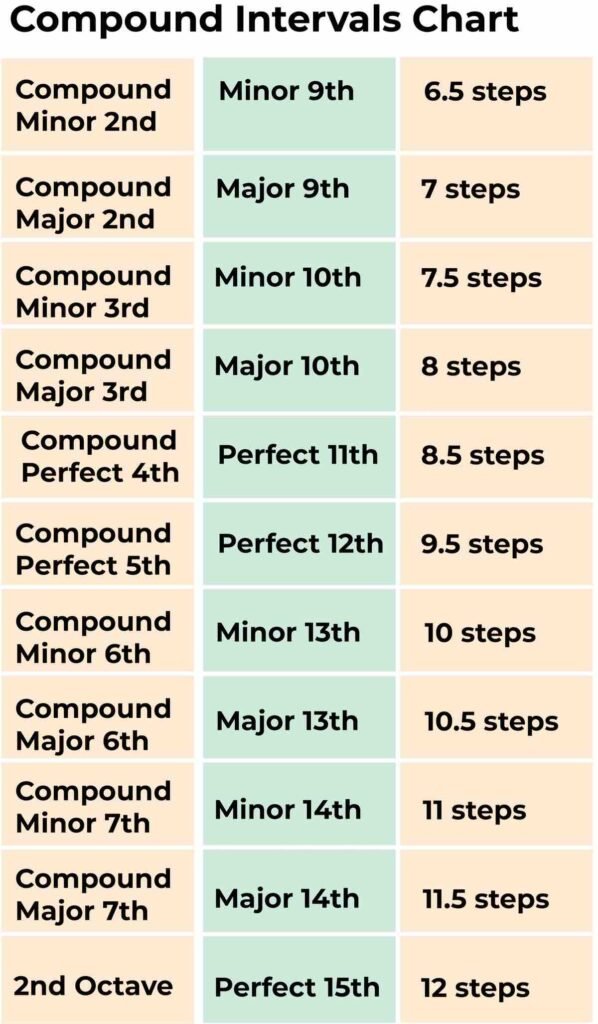

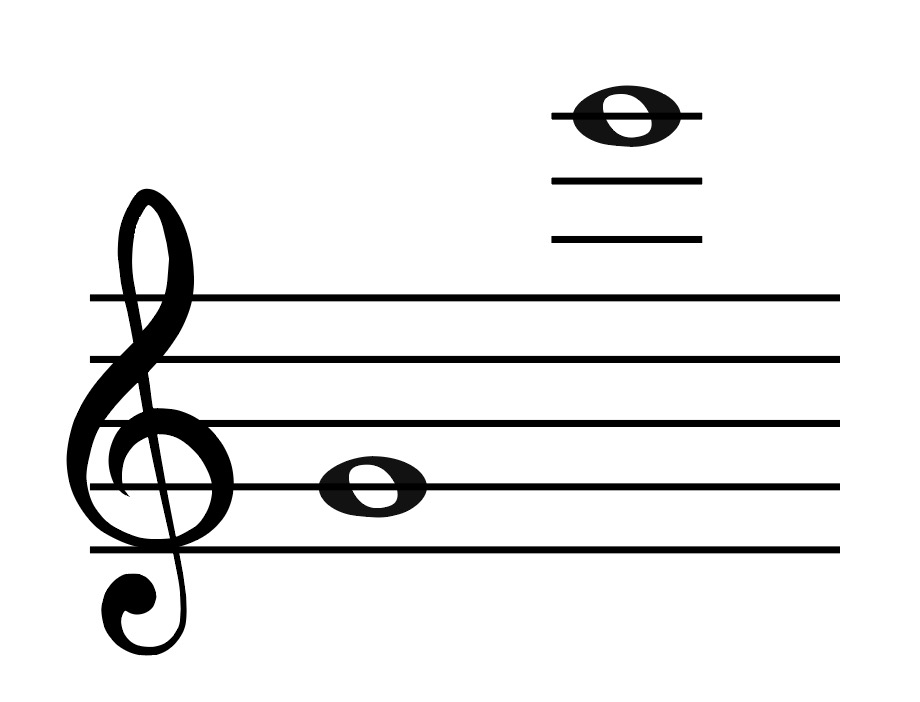

Compound Interval Chart

The chart below gives you a way of remembering each compound interval using both naming systems. The number of half-steps can also be useful to know.

Compound Major 2nd

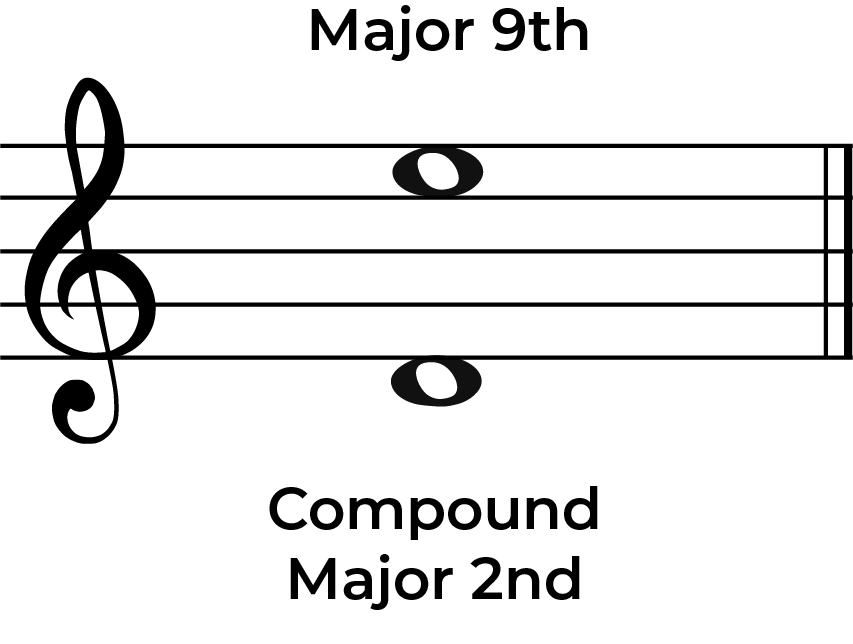

A compound major 2nd is a major 2nd but with over an octave gap between the two notes. In other words both notes are 14 half-steps between the notes. This is made up from 12 half-steps in an octave and then 2 half-steps for the major 2nd.

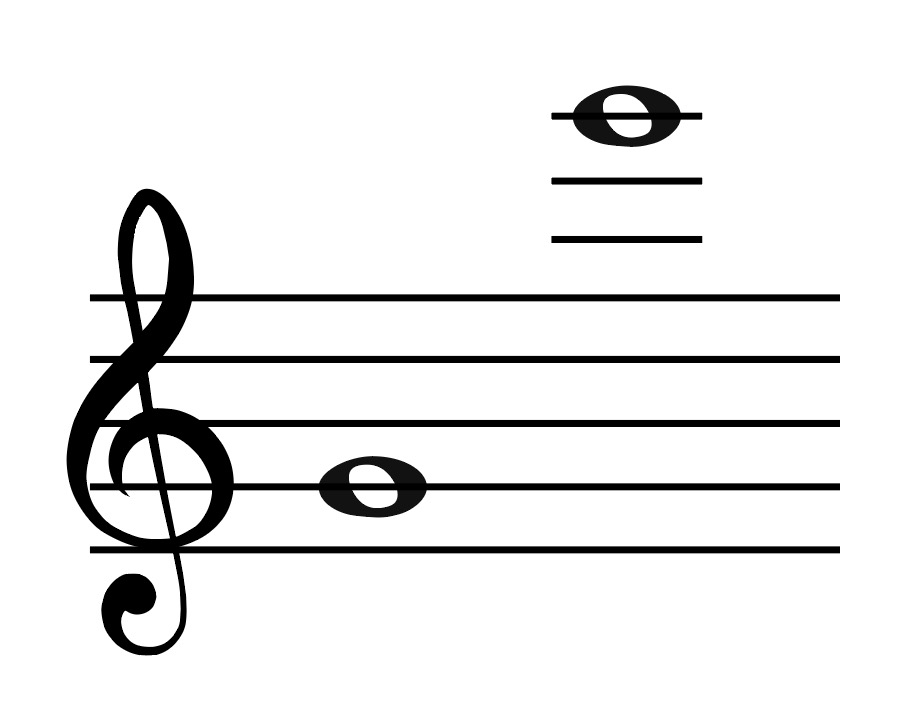

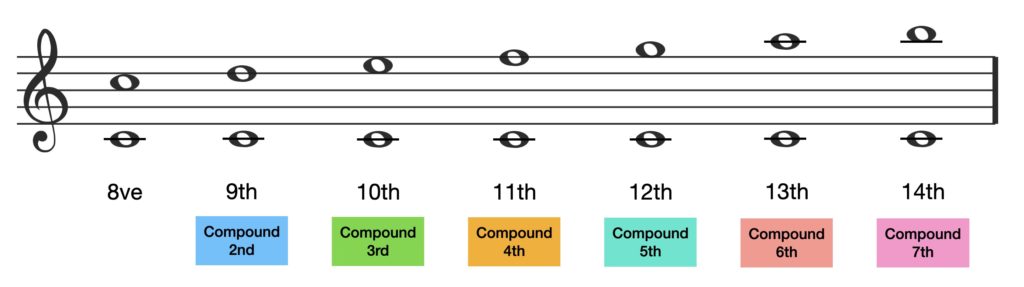

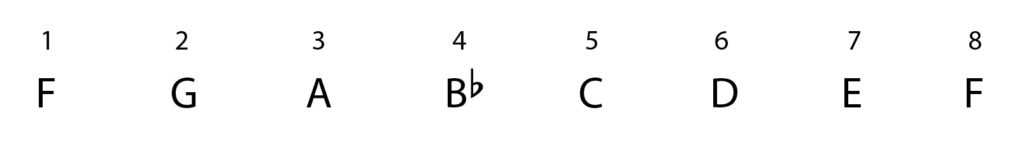

Look at the compound major 2nd below and you can see how this can also be called a Major 9th.

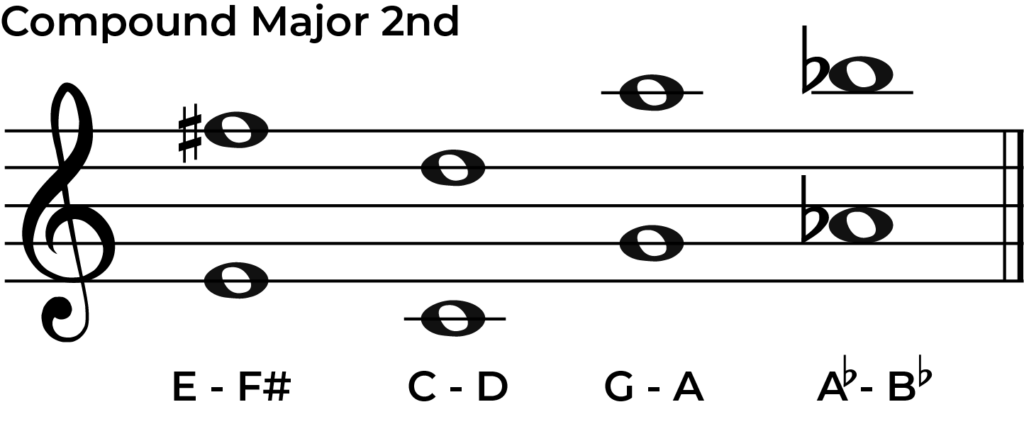

Below are some examples of compound major 2nd intervals using both names.

Compound Perfect 5th

A compound perfect 5th is a perfect 5th but with over an octave gap between the two notes. In other words both notes are 19 half-steps between the notes. This is made up from 12 half-steps in an octave and then 7 half-steps for the perfect 5th.

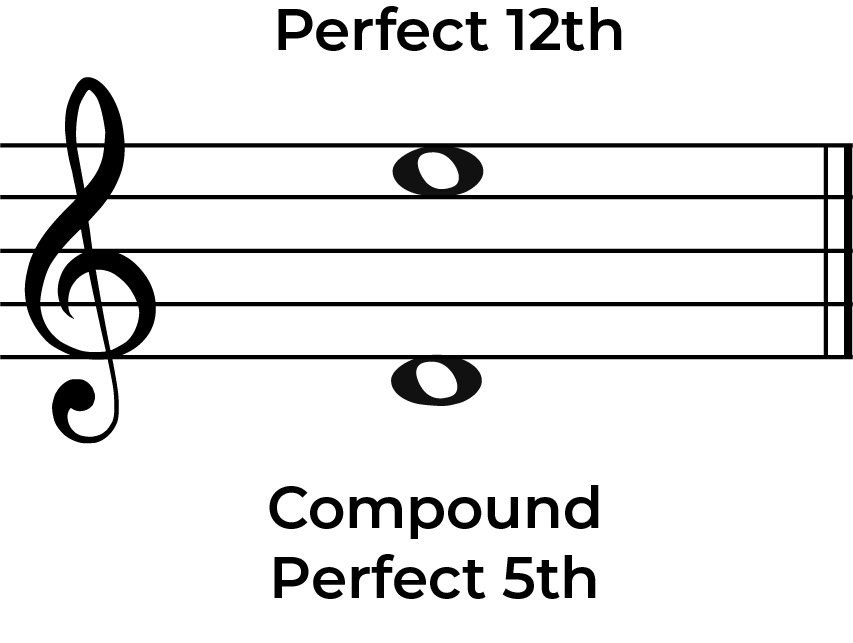

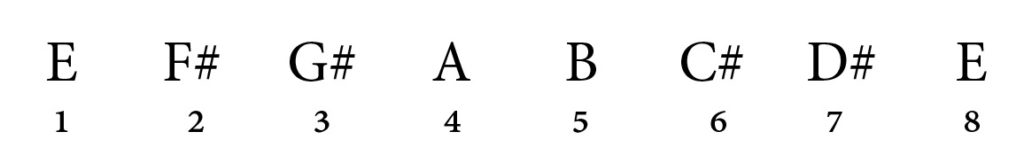

Look at the compound perfect 5th below and you can see how this can also be called a Perfect 12th.

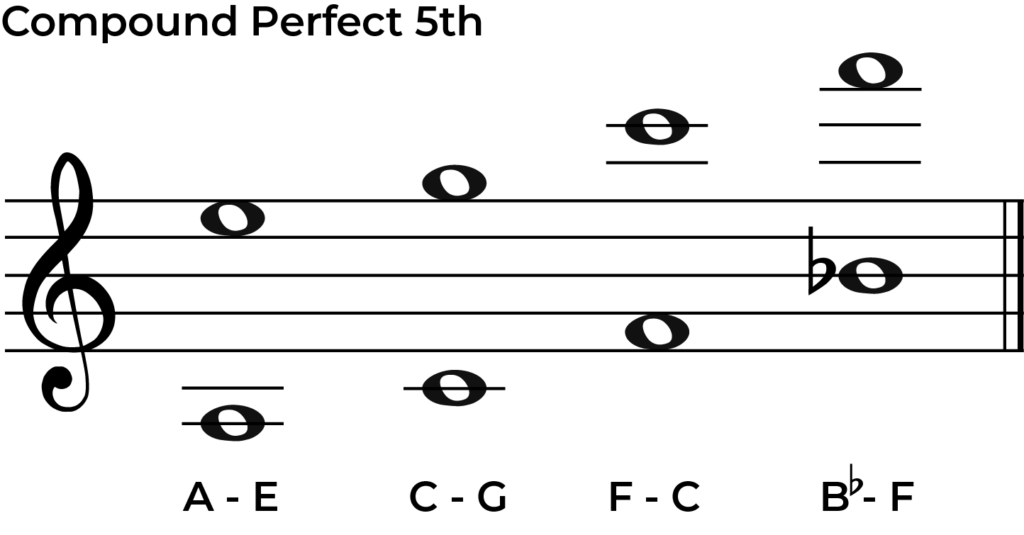

Below are some examples of compound perfect 5th intervals using both names.

How to Work Out Compound Intervals

Method 1- Counting On

We can simply continue counting on!

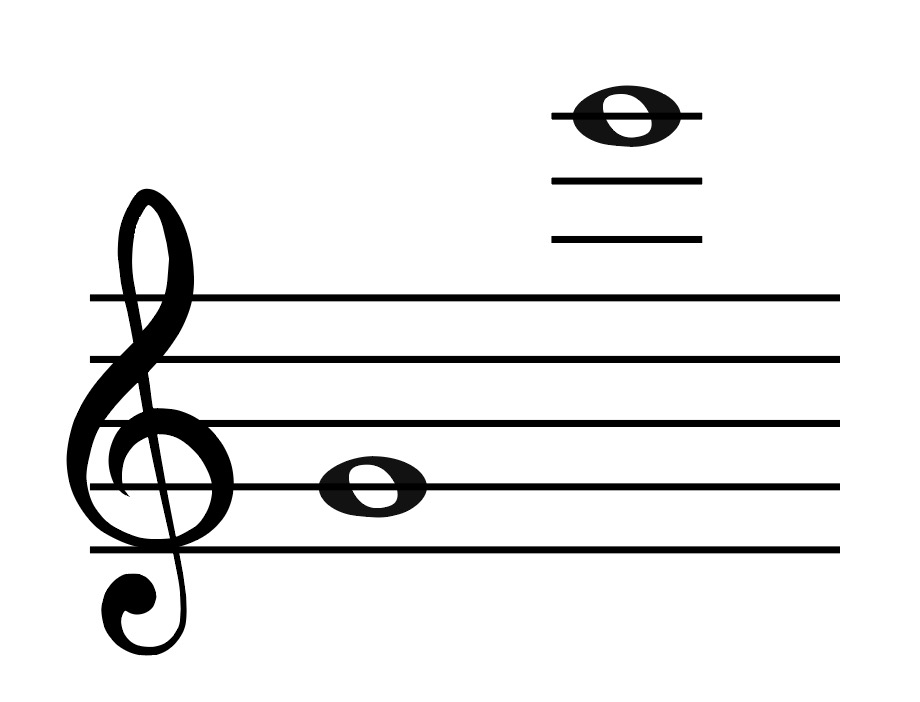

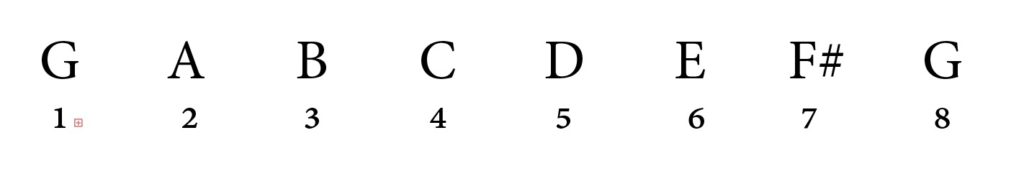

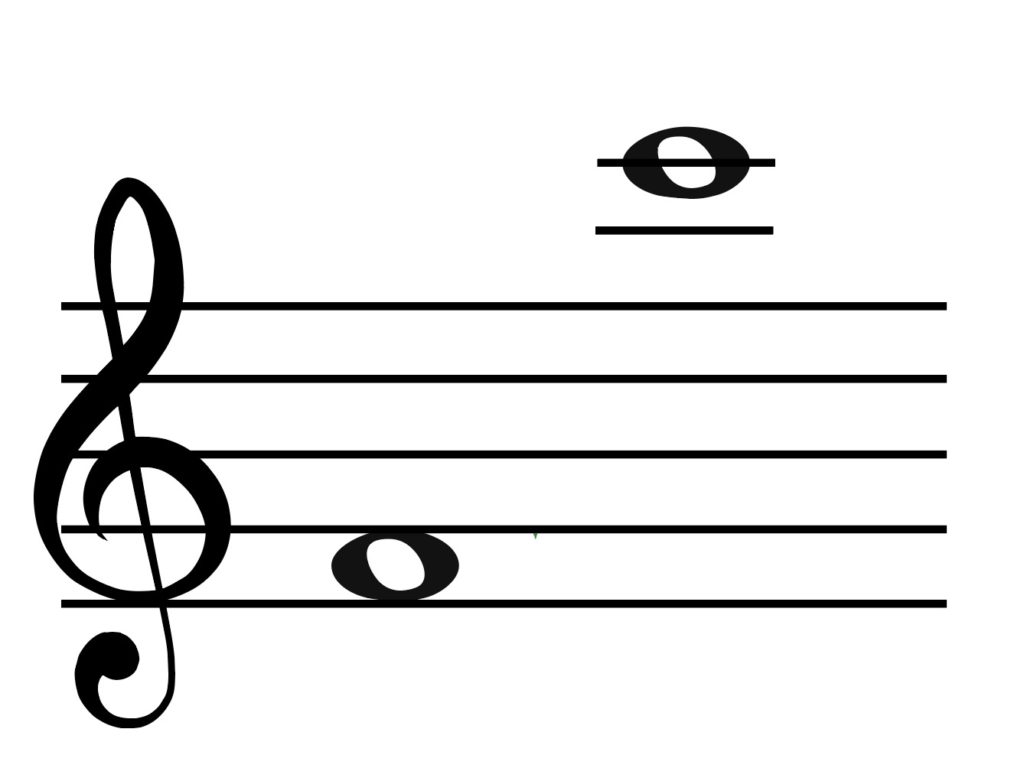

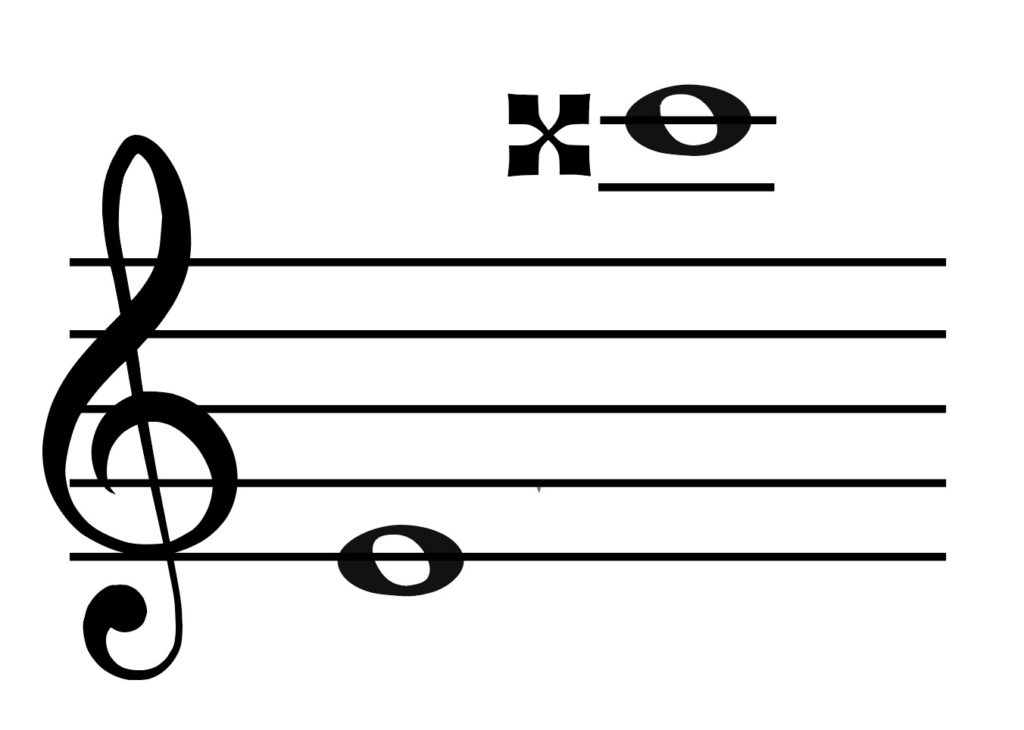

What is the distance between these two notes?

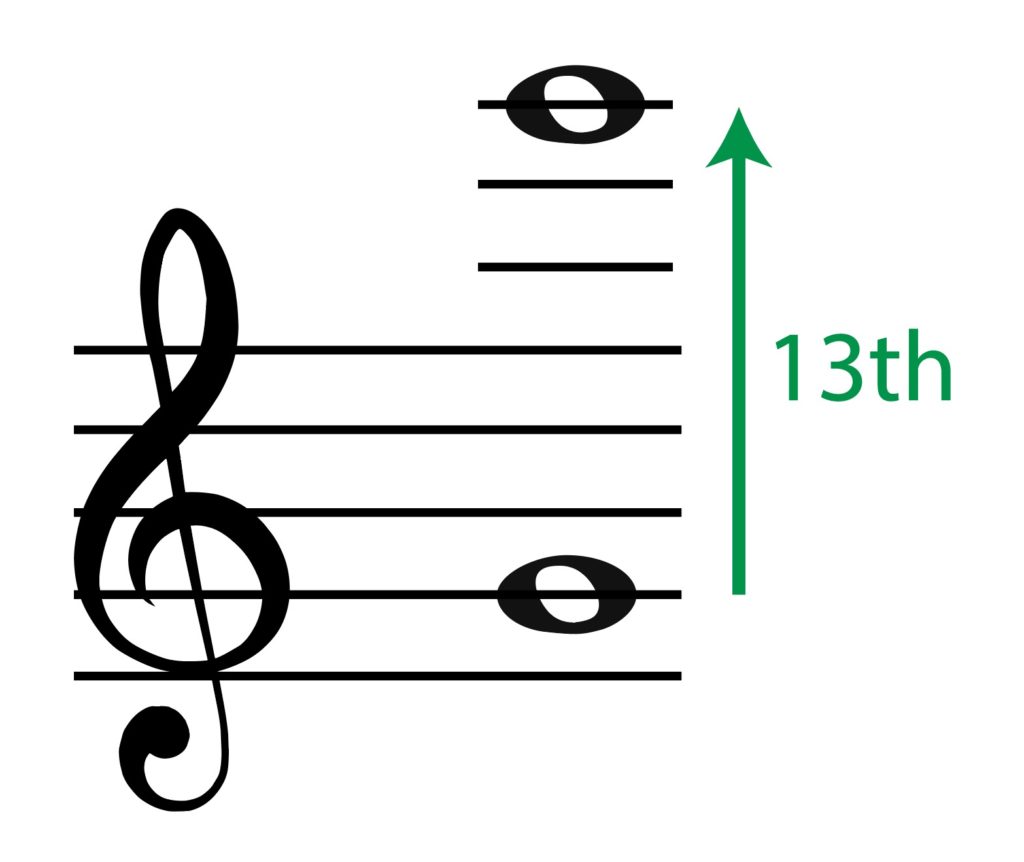

That’s correct… the distance is a 13th!

Now we simply ask ourselves the same question…

Is E natural in G major?

Yes! E natural most definitely is in G major.

This makes this interval a MAJOR 13th

However, this is not the only way to describe this interval. Another way of looking at this involves using the word ‘compound’

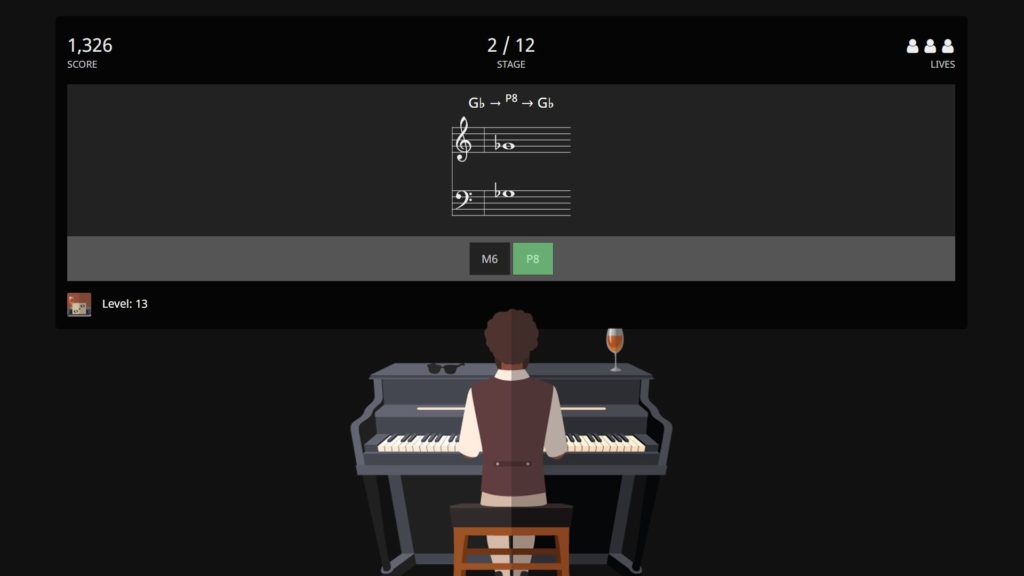

Ear Training and Intervals

To develop as a musician you’ll want to be able to recognise intervals by ear. This is where ear training comes in, as the more you practice, the better your’ll get.

My recommendation for this is Tonegym as they have a comprehensive and fun program for training your ears. It’s what has gotten the best results with for my own students.

In the ‘tools’ section of their site, Tonegym even have an interval memorizer that allows you to learn every type of interval.

For an in-depth look at ear training, here’s my full review of Tonegym.

method 2 – Use Octaves

A Compound interval is simply ‘larger than an octave’.

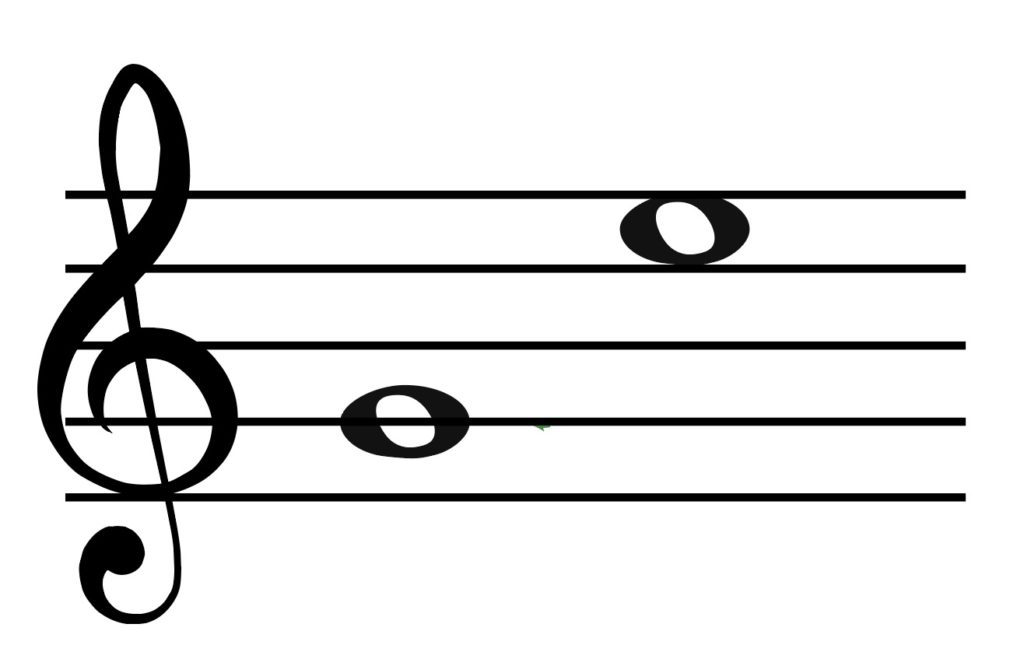

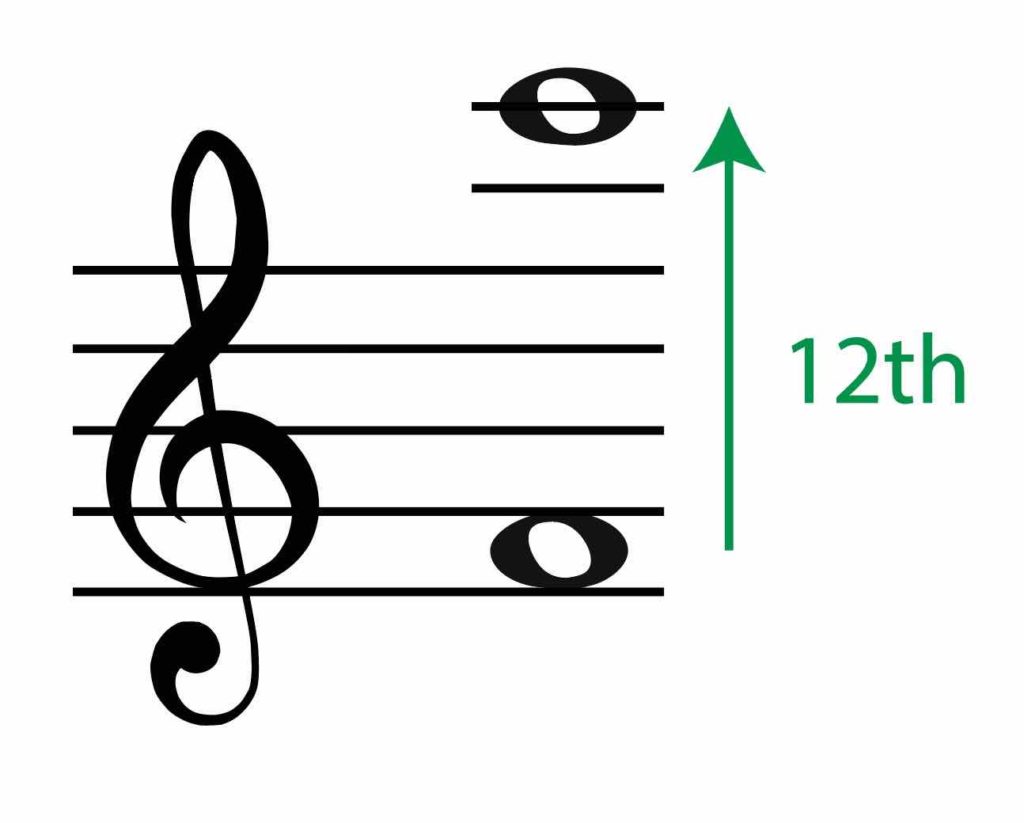

Let’s look at the interval above again…

This interval would be far easier to work out if the E was an octave lower… so let’s put this interval back to its simple state i.e. E one octave lower to make the total distance in the interval less than an octave.

Much nicer! What would this interval be?

That’s correct, it is a 6th! Is E natural in G major? Yes it is!

So this is therefore a major 6th!

Now let’s look at the original interval..

It is larger than one octave. In order to make this work we can call this a Compound Major 6th!

So as you can see there are two different ways to label an interval larger than an octave. This can be literally naming the distance between the two notes (9th, 10th, 11th etc) or working out what the interval would be if it was smaller than an octave and then writing the word ‘compound’ in front of it! Both ways mean the exact same thing.

One important thing to consider though is which intervals will be perfect and which will be in the major/minor category?

In our intervals below an octave, we know the 4th, 5th and 8ve intervals are perfect. Now if you are using the ‘compound’ method then this rule still applies – easy!

If you use the other method where you are simply counting the complete distance then you must remember that the intervals of an 11th and 12th will be perfect!

Let’s try a few examples…

What interval do we have here?

Let’s use Method 1 (finding the literal distance between the notes)

The distance between these two notes is a 12th! Is C natural in F major?

Yes it is! But remember if we have an interval of a 12th this will be PERFECT! So the answer to this question, using method 1, is a perfect 12th!

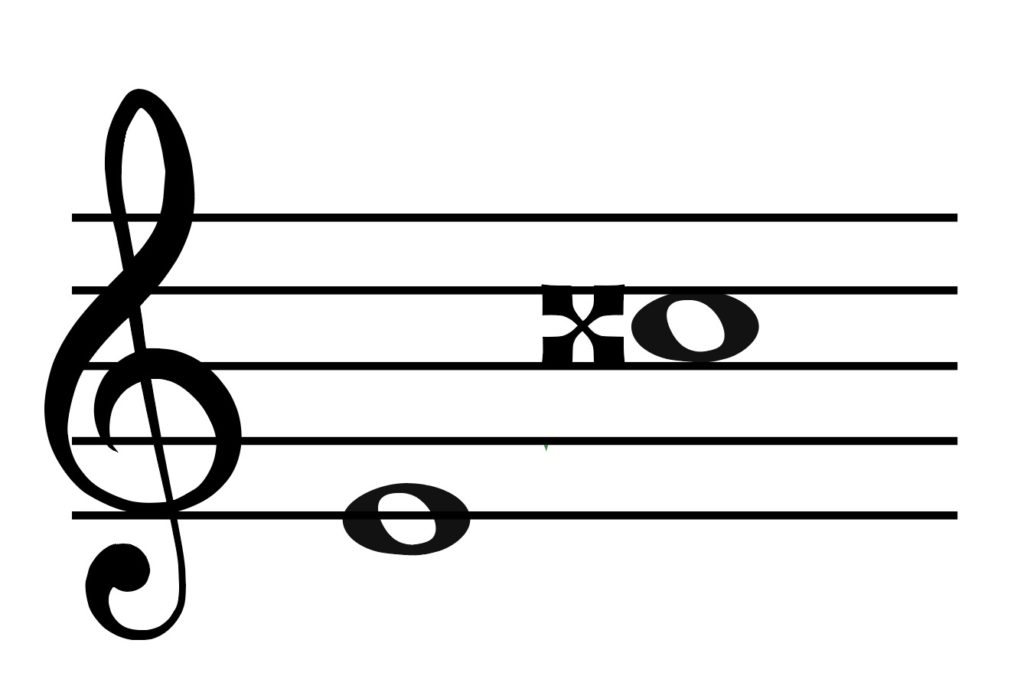

What about this one?

A Final Example for Method 2

Firstly, let’s bring this interval to it’s simple state

That is now much easier to work out! What is the distance between these two notes?

That’s correct, it is a 6th. Is C double sharp in E major?

No it’s not, but we do have a C sharp! C double sharp is just one semitone larger than C sharp, making this interval an AUGMENTED 6th.

Now don’t forget the word compound… and your final answer is:

Compound Augmented 6th!

Compound Interval Songs

It is unusual to get compound interval in a one note melody, so the best place to spot are in harmonies or orchestral pieces. These contain instrument (or voice) with different ranges therefore making it more likely that there will be intervals of over an octave.

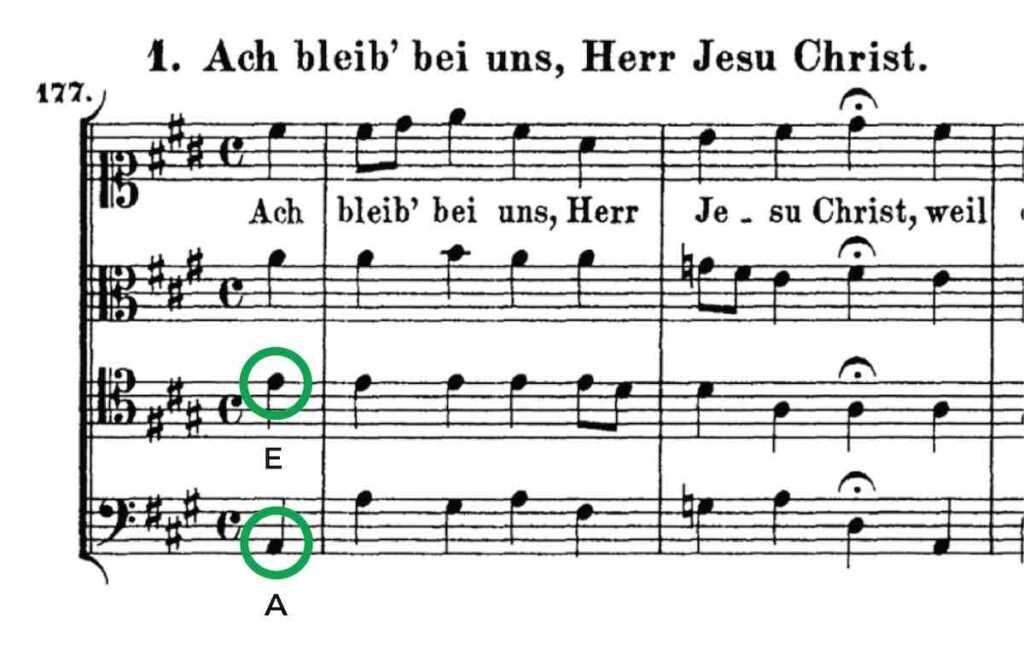

Take a look at the first part this Bach chorale. The A – E would be a perfect 5th, but as these notes are over an octave apart, the interval would be a compound perfect 5th (or perfect 12th)

You can listen to how it sounds below.

What’s next…?

- Learn more about diminished and augmented intervals.

- Put intervals together to form chords with our complete guide.